Top 10 FAIR Data & Software Things

Linked Open Data

Overview

Thing 1: Learning - Understand and practice the Semantic Web and LOD basics.

Thing 2: Exploring - Inventory of your data.

Thing 3: Defining - Define the URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) naming strategy.

Thing 4: Resolving - Consider resolvability when a person or machine visits the URI.

Thing 5: Transforming - Generate the URIs for the selected concepts and relations according to the URI naming strategy.

Thing 6: Mapping - Map your Linked Data from your newly defined namespace to similar concepts and relations within the LOD.

Thing 7: Enriching - Enrich your data with information from the LOD.

Thing 8: Exposing - Define how people can get access to your LD: a data-dump, a SPARQL endpoint or a Web API.

Thing 9: Promoting - Publish and disseminate the value of your data via visualisations and workflows.

Thing 10: Sustaining - Ensure sustainability of your data.

Sprinters

- Ronald Siebes / ORCID: 0000-0001-8772-7904 / Data Archiving & Networked Services (DANS)

- Gerard Coen / ORCID: 0000-0001-9915-9721 / Data Archiving & Networked Services (DANS)

- Kathleen Gregory / ORCID: 0000-0001-5475-8632 / Data Archiving & Networked Services (DANS)

- Andrea Scharnhorst / ORCID: 0000-0001-8879-8798 / Data Archiving & Networked Services (DANS)

Audience

We aim to provide a document which is understandable to non-experts, but that also provides specific technical references and does not downplay some of the complexities of LOD.

- Researchers (especially from the social sciences & humanities)

- Anyone interested in publishing Linked Open Data (LOD)

- Anyone interested in supporting use of LOD in research

Description

Linked Open Data (LOD) are inherently interoperable and have the potential to play a key role in implementing the “I” in FAIR. They are machine-readable, based on a standard data representation (RDF - Resource Description Format) and are seen as epitomizing the ideals of open data (see https://5stardata.info/en/). They offer great promise in helping to achieve a specific type of machine-executable interoperability known as semantic interoperability, which relies on linking data via common vocabularies or Knowledge Organisation Systems (KOS). This document attempts to demystify LOD and presents_ Ten Things_ to help anyone wanting to publish LOD.

Although this list of_ “Things”_ are presented in a roughly linear order, preparing and publishing LOD are iterative processes. Expect to go back and forth a bit between the_ Things_, and take the time to double check that your progress matches your desired end result. Some_ Things_ can be executed in parallel; you will also notice recurring themes (e.g. sustainability and licensing concerns) that need to be considered throughout the workflow.

These Things are based on our own practical experiences in publishing LOD in various interdisciplinary settings, e.g. the Digging into the Knowledge Graph project (http://di4kg.org). Our goal is to complement existing scholarly reports on LOD implementations (e.g. Hyvönen, 2012; Hyvönen, 2019; Meroño-Peñuela et al, 2019), other workflow models (see W3C Step #1), and the authoritative “Best Practices for Publishing Linked Data” of the W3C, which we cross-reference (as W3C Step #X) wherever appropriate. We include visualisations, suggest readings, and highlight other projects to make this guide understandable and usable for people across disciplines and levels of expertise. However, it is important to note that semantic web technology is a complex scientific field, and that you may need to consult a semantic web expert along the way.

Things

Thing 1: Learning - Understand and practice the Semantic Web and LOD basics

Semantic web technology (which underlies LOD) is complex. It requires not only a new data model (Resource Description Framework, RDF) but also infrastructures for storing and linking data as well as algorithms for retrieving, enriching and reasoning across those data.

Understanding LOD begins with understanding the Resource Description Framework. RDF is a standard format defined by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) that can be easily interpreted by machines.

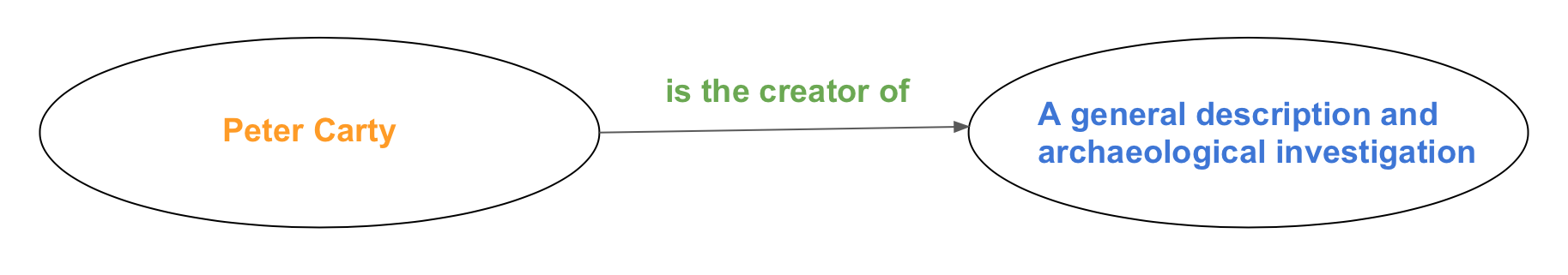

RDF statements are called “triples” because they contain three pieces - subject : predicate : object. RDF data is modelled as a “labeled graph” which links description of resources together. Subjects and objects are nodes, predicates are links.

Figure 1: An example of a triple

RDF is notated as a list of these statements (the triples) that describe each piece of knowledge in your dataset. This list of statements can be thought of as a large indexing file to your data.

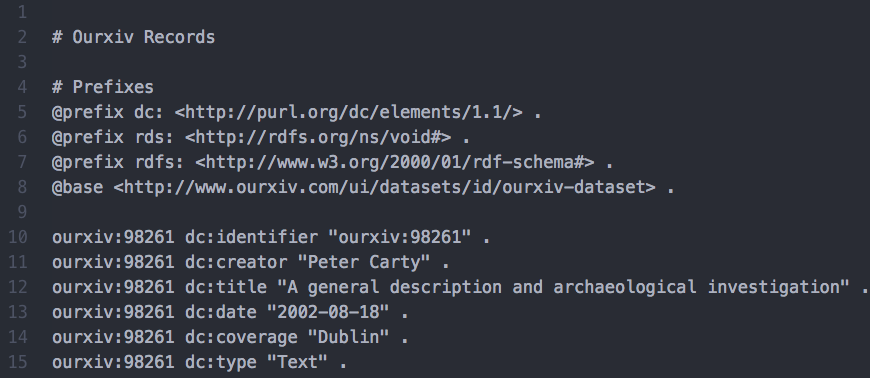

There are different formats for creating RDF. Popular formats include RDFa, RDF/XML, Turtle and N-Triples. Although these formats are slightly different, the meaning of the RDF statements written with them remains the same. In our examples, we use the Turtle format and wrote the code using Atom, a collaborative text editor. (See W3C Step #3)

This is a section of RDF representing an example dataset, which we use throughout the text.

Figure 2: A screenshot of an RDF representation

The graph structure of RDF offers benefits over typical database structures. Creating new subjects and predicates is far less tedious than creating new fields and linking tables, as is common in database design. Storage in RDF is also more compact. Perhaps most importantly, RDF enables specific ways of questioning your data that are not possible with other structures. In a triple, the predicates (the links) also have meaning and thus are semantically encoded; this facilitates executing more complex operations (known as “semantic reasoning”) on the graph. In our example (see Figure 1; Figure 2), the role of “Peter Carty” as “creator” of the dataset is spelled out, and so can be differentiated from other possible roles - such as being a contributor or a collaborator. In the end, RDF is simply another way of expressing your data.

Activity: Who better to introduce you to the concepts ot LOD than Tim Berners-Lee, founder of the World Wide Web? View these videos for an overview of the topic:

- Tim Berners-Lee on “The Next Web”: http://www.ted.com/talks/tim_berners_lee_on_the_next_web

- Tim Berners-Lee at the GOV 2.0 expo (“bag of crisps”): https://youtu.be/ga1aSJXCFe0

- Then, check out how Google uses this same technology in the Knowledge Graph: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mmQl6VGvX-c

Putting data into RDF is one ingredient in working toward LOD. RDF statements must also be expressed as Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs - see Steps 3-6) in order to link them to other data. It is possible to have Linked Data (LD) living on internal servers that are not a part of the larger Linked Open Data Cloud (LOD Cloud). In order to publish data to the LOD Cloud, URIs must be readable, or resolvable (see Step 4), not only internally, but also to outside sources.

Activity: Visit the LOD Vocabularies https://lov.linkeddata.es/dataset/lov/ and see the different types of things that can be linked to. Eventually you will be linking your data to some of these vocabularies (see Thing 7). Can you identify datasets that contain concepts similar to those in your own dataset? (For example, if you have data about cities, you may want to look for datasets with information about cities, e.g. DBPedia).

Thing 2: Exploring - Inventory of your data

2a: Identify relevant concepts from your datasets that you want to expose as Linked Open Data (LOD)

The first step in expressing your data in RDF is to identify the concepts in your dataset that you would eventually like to expose and link to the LOD Cloud. It will most likely NOT make sense to expose all of the concepts that exist in your data; you will need to be selective. (See W3C Step #2)

Activity: Take an inventory of your dataset. What type of data do you have? What structure (e.g. XML, a database) are they in? Based on your exploration of the LOD Vocabularies in Thing 1, think about which concepts it makes sense to eventually link.

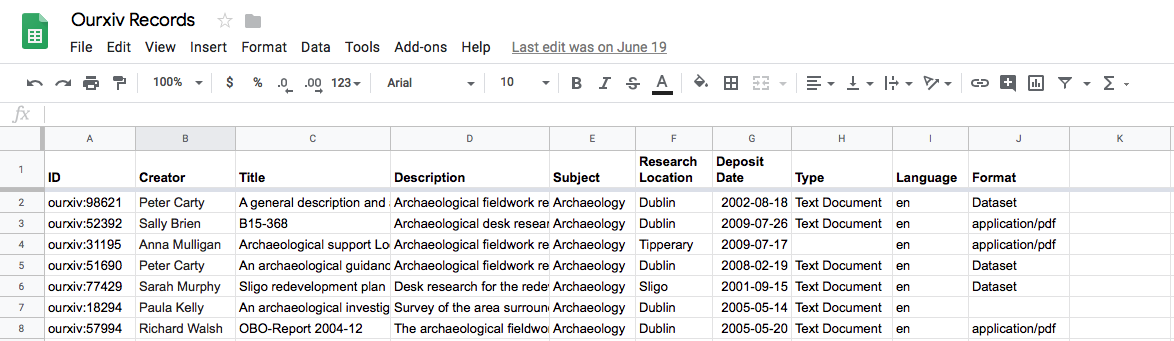

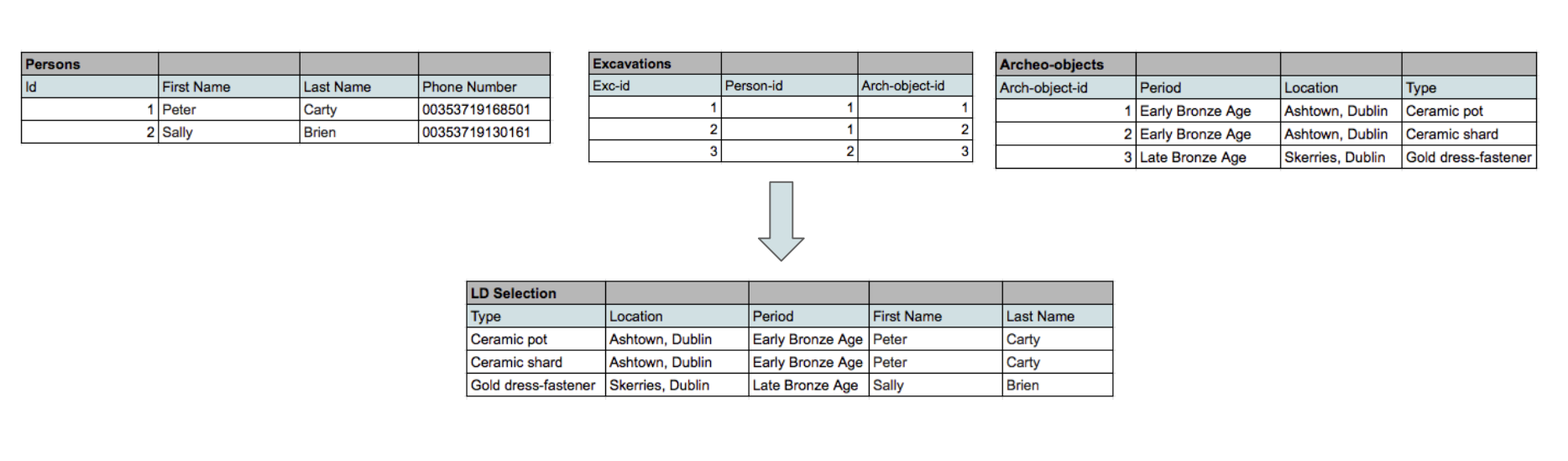

We take as our example an archeological dataset based on data found in the EASY data repository of DANS. The dataset contains archaeological records with ten attributes listed for each record; the dataset has been anonymised for the purpose of this example. As we will discuss later, not all of the concepts in the dataset are interesting to share.

Figure 3: The original data in tabular form

It is also important to consider who owns the data in this step. In an archive, each dataset can have information about the license status. Are the data listed as being open, or is there a requirement for you to request permission or acknowledgement in order to use the data? Ownership and licensing are also important to consider for your own data.

Activity: Think about your own data. Are you the data rights holder for all parts of your data? If not, identify any licenses that may restrict if you can expose and link the data to the LOD Cloud. (See W3C Step #1)

Identifying relevant concepts and relationships is a step that is vital for everyone, both novices and experienced computer scientists. Computer scientists use visual tools to “model” their data, such as Visio and Draw.io, but you could also create a simple list of the concepts that you would like to expose and link.

Activity: View the introductory tutorial for Draw.io and experiment using the tool by visiting this link: https://www.draw.io.

One side remark: The term ‘concept’ has a specific meaning in various disciplines. In the context of computer science, ‘concept’ means a class, i.e. a knowledge representation (of objects, individuals, actions, etc.). In general, ‘concepts’ are abstractions made to order things. They are represented by terms (Dextre Clarke, 2019) An ensemble of concepts is often represented in the form of controlled vocabularies, schemas, or ontologies, more generally known as Knowledge Organisation Systems (KOS).

This means that, if your data are structured in a database format, the headers or fields represent your concepts.The actual cell values are the concrete instantiation (or specific examples) such as phenomena or observations for these concepts. This is a general rule of thumb; you could also have cases, however, in which your cells are concepts themselves.

Often not all of the elements in the dataset are things you wish to share. (We discuss this further in Thing 5 when we address how to filter your dataset). We have selected five concepts from our example dataset to demonstrate the difference between concepts and instances.

Concepts from out dataset:

| ID | Creator | Title | Research Location | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Instances of each of these concepts:

| ourxiv:98621 | Peter Carty | A general description and archaeological investigation | Dublin | 2002-08-18 | Text Document |

Figure 4: Examples of concepts and instances in our example dataset

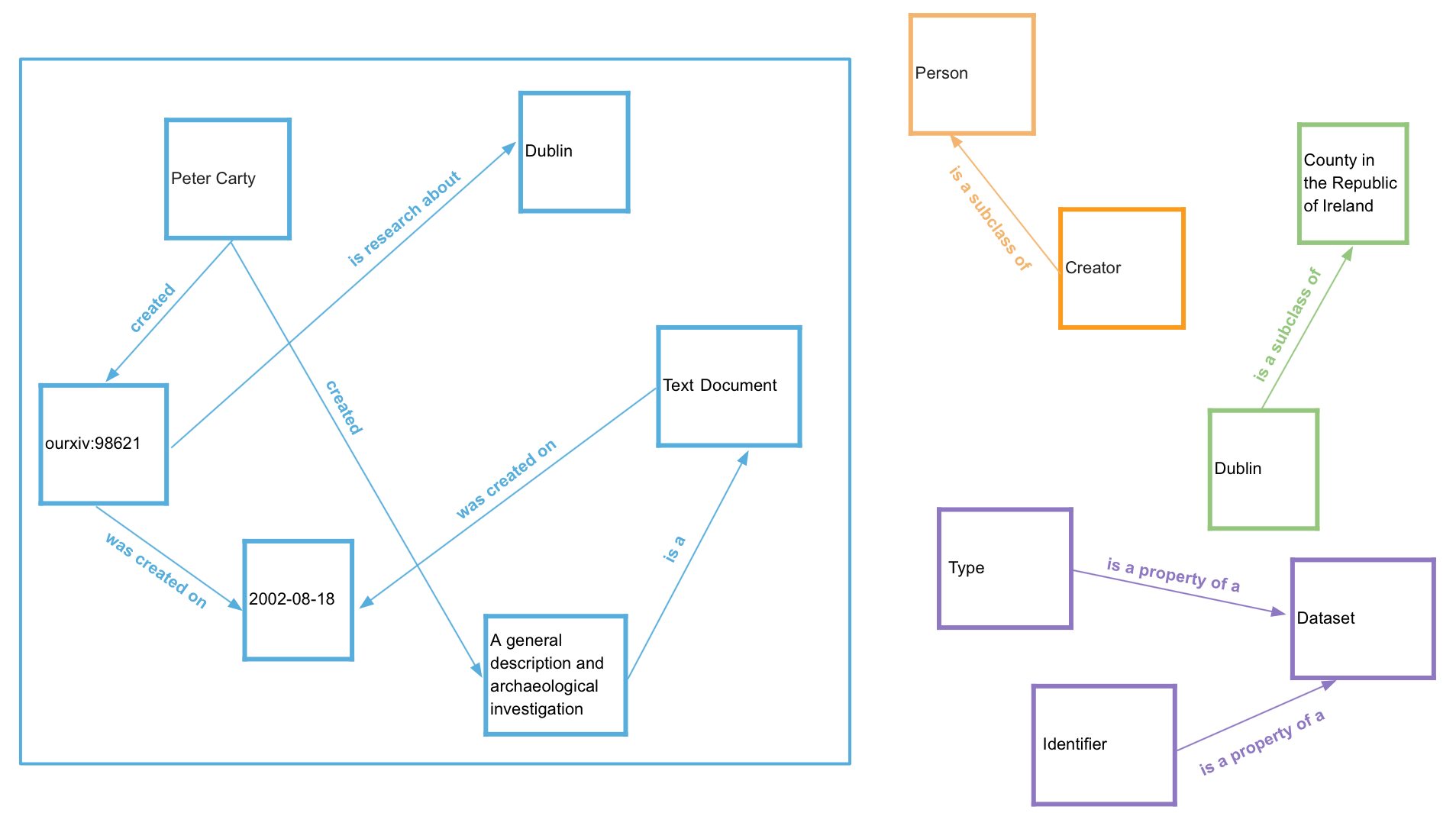

2b: Identify relevant relations from your datasets that you want to expose as Linked Data (LD)

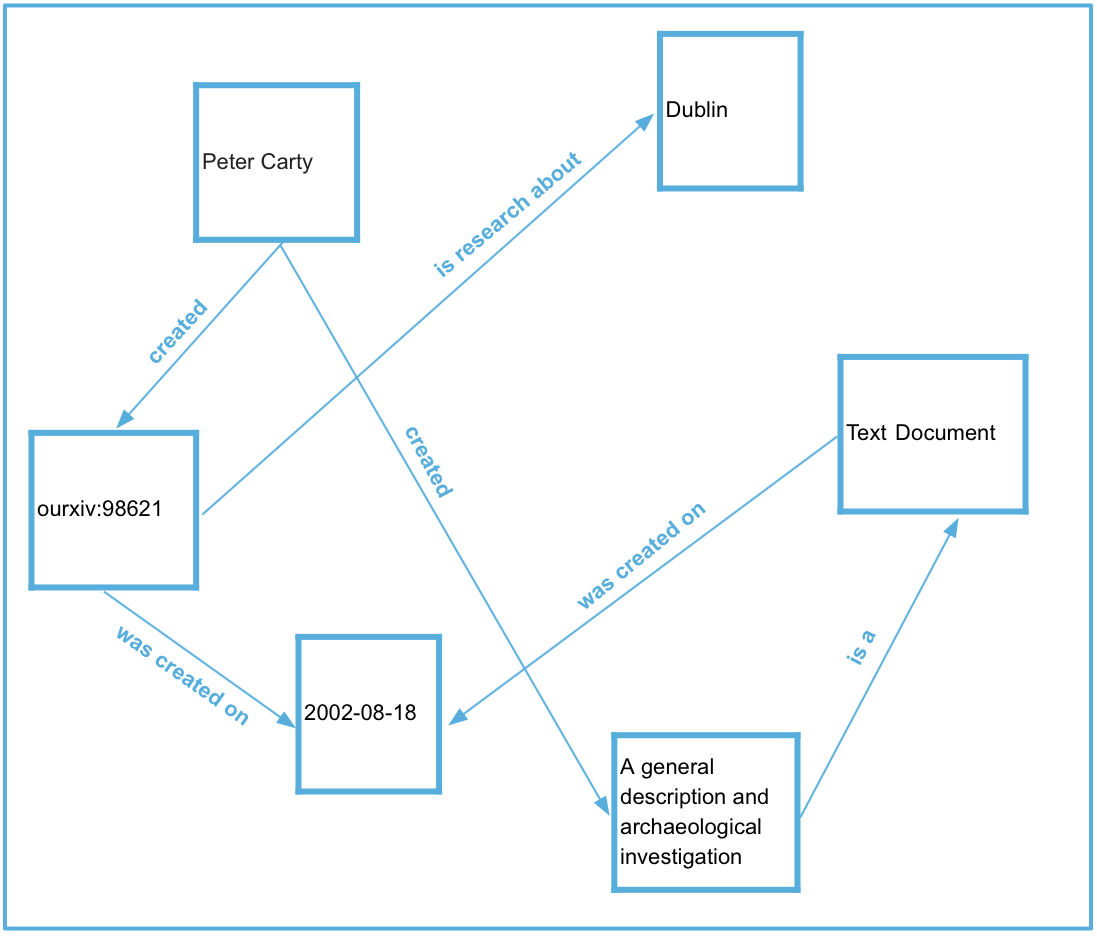

Having identified the concepts in your dataset, you now need to identify the relations (i.e. what later becomes predicates or links) between those concepts.

The relations are often determined by the structure of the database itself; however, sometimes the column or row headers can also express relations.

Here is a data model which shows some of the relationships between the concepts in our example from 2a. We can see the subject : predicate : object structure.

Peter Carty created A general description and archaeological investigation

Visualising your data model in this way can also help with understanding where there are relationships which may have been hidden. Once you have a model of the concepts and relationships you would like to link and expose, you are ready to begin defining them as URIs, which will be explained in Thing 3.

Activity: Examine the below model of our dataset. What might a possible relationship between ‘Peter Carty’ and ‘Dublin’ be?

Figure 5: An example of modelling data

Thing 3: Defining - Define the URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) naming strategy

3a: Define a suitable and durable namespace

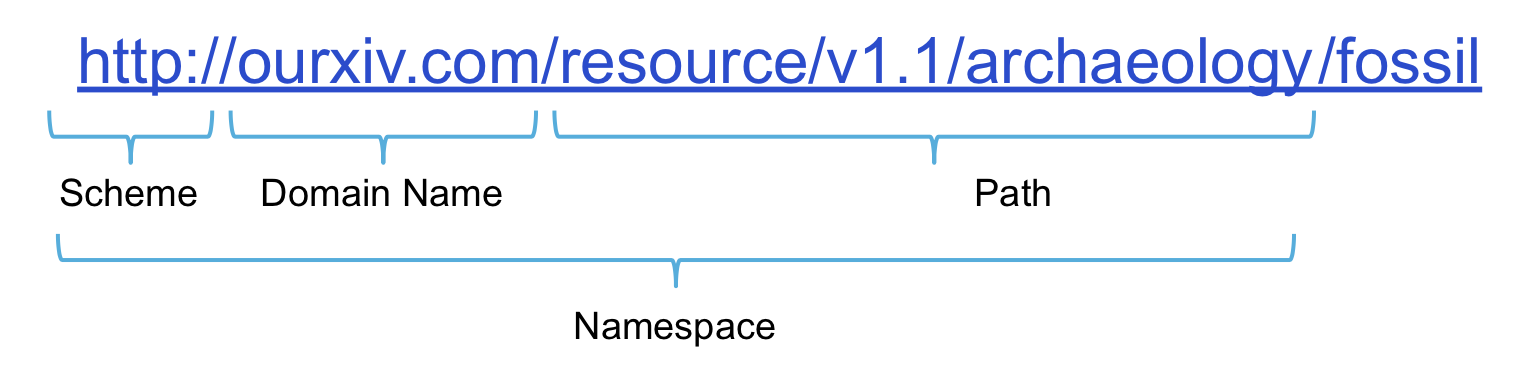

The URI is an address that a machine can use to find exactly the right piece of information on the World Wide Web. (You are familiar with this idea already - think of the URL of any website). A URI consists of three parts: a scheme, a domain name and a path. The domain name plus the path are known together as the namespace. Defining a namespace is extremely important in LOD, as it allows machines (and humans) to tell the difference between identically named elements from multiple datasets. (See W3C Step#5)

Figure 6: Example of the three parts of a URI

You will first need to choose a domain name to use for the URIs you will create. It is important to think about the sustainability of the domain name that you use. URIs should be persistent and not change over time. If you plan on using a domain name that is part of a project, think about how (or if) that website will be maintained after the end of the project. It is always better to choose something that you are sure will stand the test of time (see W3C Step #5), such as institutional domains. Institutional domain names have the added benefit of conferring a sense of authority. That is, a domain name of “harvard.edu” suggests more authority than a domain name of “jane_smith.com”. (If you are unsure about your institutional options, check with your local IT professional for guidance).

The remainder of the URI is the path. You can think of the slashes in the path like folders and sub-folders that are used to organize information in a manner that is understandable to both people and search engines. We have further recommendations for constructing the path in steps 3b and 3c.

Activity: To further prepare for creating your own URIs, read “The Role of Good URIs for Linked Data” from the W3C guidelines.

3b: Consider a versioning strategy that reflects past and future modifications of your LD in the URI Path

Datasets are not static; they are often updated and modified with new versions. We recommend that you include versioning as part of your namespace (in the path) to make it perfectly clear which version of your data you are referring to.

The W3C also recommends using vocabularies that provide versioning control. Vocabularies are the definition of concepts, relations and their mutual order. Vocabularies also change, as they are developed and edited. Using a vocabulary with versioning control ensures that if the vocabulary changes, you point to the _right _version of it. (See W3C Step #6). Concrete observations or instantiations of a vocabulary can also be reclassified. If this happens, you also need to indicate the change at this level.

There is no firm policy on this problem yet. Although in most cases only a small percentage of concepts and relations change between different versions, our proposal is to include the version information in the URI, such as in this example:

http://ourxiv.com/resource/v1.1/archaeology/fossil

We believe that this strategy will help your “audience” - those who map to your versioned vocabularies - from doing unnecessary updates. We imagine the following scenario: when anybody uses the URI without the version tag (shown in red in our example above) a “smart” lookup service would return versioning information about the concept ‘fossil’, it would also return the preferred version, and the versions where there were changes to this concept.

Changes in vocabulary or instantiations, but also any other changes that you make ( i.e. mapping and enriching, which we will discuss in later things) can be documented or “logged” and described with a commonly shared vocabulary (Moreau & Groth, 2013). This is also called provenance information. Compared to versioning, it is like a meta operation on changes concerning the whole or parts of the graph. The versioning we discuss above concerns what has been changed in the knowledge representation structure itself, but does not focus that much on who did it, when and by which process.

3c: Decide how the concepts and relations are represented by its unique identifiers which are part of the URI.

We also recommend that you construct your URI in a way that it reflects the meaning of the concepts and relations that you identified in Step 2. This will make it much easier for people to interpret the URI and understand the link.

Rather than using a long string of numbers in our example URI, we used the URI to indicate the relationship between the thing that our data describes (a fossil) and the description of that thing.

http://ourxiv.com/resource/v1.1/archaeology**/fossil **

This involves thinking about how to distinguish between objects in the real world and the webpages describing those objects. Use specific patterns to represent properties, individuals, and classes. For example:

http://ourxiv.com/resource/v1.1/archaeology/fossil ← Thing

http://ourxiv.com/data/v1.1/archaeology/fossil ← RDF data

http://ourxiv.com/page/archaeology/fossil ← HTML page

Activity: Using what we have discussed about best practices for creating a URI, draft a few URIs to describe your own data.

Thing 4: Resolving - Consider resolvability when a person or machine ‘visits’ the URI.

If someone were to put your URI into a browser, what would she get back? A URI is “resolvable” if anyone, regardless of their own domain, can put it into a browser and see a result. Please note, that the example URI’s we have constructed so far are not resolvable!

Activity: Take a look at example.org. Is this domain resolvable? Why or why not?

Not every domain is resolvable. The domain in the above activity is not resolvable, but is rather just a placeholder. Remember, you gain authority and trust from other users when your URIs are resolvable and lead to information.

In terms of LOD, it is important that the information that is returned describes the concept in the URI entered in the browser. The information returned could be a snippet of RDF with, for example, information about properties, classes or provenance.

A basic implementation of an RDF URI resolver is the Urisolve server. The Urisolve server takes a URI as input and returns a simple list of triples that all have the URI somewhere in each statement. This implementation assumes that there is an HDT (Header, Dictionary, Triples) or SPARQL endpoint that hosts your RDF data. Virtuoso is a well known open-source RDF datastore that includes a SPARQL endpoint. HDT is a binary format for RDF which has major performance benefits.

Activity: Visit http://www.rdfhdt.org/ to learn more about HDT and supporting tools.

Thing 5: Transforming - Generate the URIs for the selected concepts and relations according to the URI naming strategy.

Steps 1-4 are primarily planning steps; in principle, you could actually do them on paper. Step 5 requires software, tools and/or scripts to transform your data into Linked Data.

Your exact approach depends a lot on your particular situation; the format of your data, the size and the available (programming) expertise are the main factors.

The below workflow suits many situations:

1: Filter your data

In Thing 2, we mentioned that it will most likely not make sense to share all of your data. Filtering your data involves creating a new temporary dataset that contains only those concepts and relations that you want to expose as LD. If your data is in a database like PostgreSQL or MySQL, it is often easiest to write a SQL command that generates one new temporal table containing the union of selected columns from the various tables. If your data is in a spreadsheet like Excel, you can create a new sheet via macros and filters. Note that you should try to keep this filtering and generation process as automated as possible and save the macros or SQL for future version conversions.

Figure 7: An example of filtering data

Activity: Based on your work in Thing 2, create a temporary dataset containing only those concepts and relations that you want to expose as LD.

2: Bridge your prepared data to your tool

There are basically two ways for an RDF generation tool to work with the table from the previous step: 1) set up a connection between the data store and the tool, or 2) serialize the data to a format that the tool can use.

2a: set up a DB connection

Tools like Ontop can connect directly to your database and uses transformation rules to create Linked Data, or even a SPARQL endpoint to your live data.

2b: Serialize your data

Serialization is turning your data from the format you usually interact with to a series of bits. Based on your data format, most tools and databases have the functionality to store tables in CSV format. Please be aware that encoding can be tricky especially with special character sets.

3: Use tools to transform your serialized/connected data into LD

Depending on the previous step, the selected tool directs the way how your data will be transformed into Linked Data.

Thing 6: Mapping - Map your Linked Data from your newly defined namespace to similar concepts and relations within the LOD

Most likely there will be concepts and relations in your fresh LD dataset that are similar to concepts and relations in the LOD. The challenge in this step is to 1) find them, 2) make a selection based on a quality metric and 3) select the schema to express these mappings.

1: Finding related concepts and relations

The ‘Linked’ aspect of Linked Data is the focus of this point. In this exercise you browse online resources to find vocabularies and schemas that have concepts and relations similar to those you have created.

Activity:

- Explore the following public sources to find Linked Data related to your own: The LOD Laundromat, the Linked Open Vocabularies portal and BARTOC.

- Next, look at the following domain-specific resources: GeoName for locations and Getty AAT for excavational objects like Etruscian Pottery.

- Are there any other domain-specific sources for vocabularies that you know of that could be relevant for your data?

Note that, although preferred otherwise, the external concepts you wish to link to themselves do not need to be designed as Linked Data. For example, a researcher mentioned in your database can have a persistent identifier in ORCID and a publication can have a DOI.

2: Sort and make a selection from the sources found in the previous step

The decision depends on many factors, such as your audience (if, e.g., it needs to be multilingual), the coverage with your own concepts (i.e., exact match is preferred to broad superclasses), the authority of the external source (who developed it and maintains it), etc.

3: Selection of the mapping schema

There are different ‘flavours’ regarding mapping concepts and relations. The choice is made primarily based on the inferencing and other logical reasoning requirements, as we detail below.

3a: RDF and RDFS

The de-facto linked data format is RDF. In RDF one can specify that an instance is of a certain class, like a cat is a type of animal. RDFS is an extra logical expressive schema that allows one to bind a property to a domain and range, for example the employer relation is between the domain: person and range: organisation. RDFS provides the means to specify sub-classes, e.g. student rdfs:subClassOf person, and sub-properties, e.g. hasSibling rdfs:subPropertyOf hasRelative. Unfortunately, neither RDF nor RDFS offer an option to state equality between concepts or relations. For that we have OWL and SKOS which we cover next.

3b: The OWL variants

The W3C-OWL stack (e.g. OWL-Lite, OWL-full OWL-DL) extends RDFS with additional reasoning options grounded in formal logic, which has as an advantage that more automated checking and derivations can be done but is also for many people difficult to learn and adds more computational demands to the reasoning backend. The most popular owl statement is the property owl:sameAs which as expected expresses equality between two instances (e.g. “Bill Clinton” and “William_Jefferson_Clinton”) or classes (e.g. “Area” and “Region”).

3c: SKOS

The popularity of SKOS perhaps lies in the fact that it has no formal grounding and people use it to express all kinds containment relations. For example the skos:broader property is used to express a subclass relation (mammal skos:broader animal), a subregion (Texas skos:broader USA), subperiod (baby-boom-period skos:broader 20thCentury) etc. Despite the lack of formal grounding, most humans do understand the inherent reasoning and can develop in retrospect applications that properly deal with these mappings.

Having a good idea about which concepts in your own data you want to expose and which concepts are already published as Linked Data helps in the decision making process for selecting a mapping schema. Likewise you can revisit your data model and see if there are better ways to define the relationships between your concepts.

Activity: Study the below figure. On the left is the data model from 2b and on the right we can see some concepts which we have identified as relevant to map to our dataset. Can you identify which concepts on the right would be mapped to which parts of our data model on the left?

Figure 8: An example of a modelled dataset (right), with some potential external concepts for the data to be linked to (left)

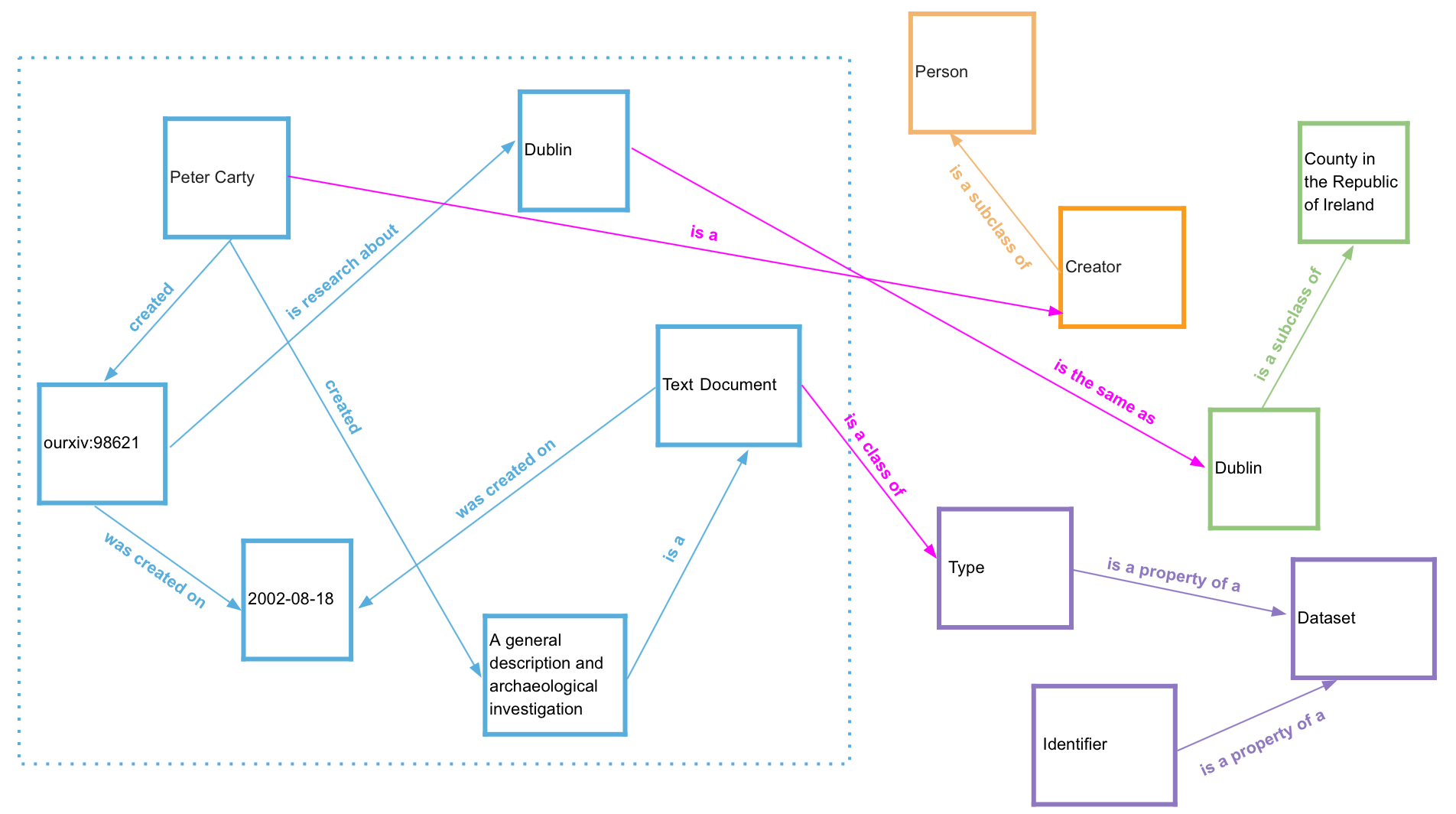

Thing 7: Enriching - Enrich your data with information from the LOD

The enrichment process is very similar to the mapping, with the subtle difference that the goal of mapping is to connect your data to existing Linked Data, and enrichment is to describe your data with Linked Data. Although not set in stone, the mapping process uses a well known set of properties that results in a linkset of similarities in RDFS (e.g subClass), SKOS (e.g. exactMatch) and OWL (e.g. sameAs). The enrichment process has a wider scope on both the selection of properties and objects. Key is that the enrichments are relevant for the goal of sharing your data.

Activity: Imagine that you are a producer of chemical compounds. The molecular weight, structure, boiling point, etc. for different compounds may be relevant properties for your data. Take a look at ChEMBL and explore how it could be useful to you.

Similarly, if you work for a library, you can enrich your collection with concepts from library classification systems like LCC, UDC and DDC.

Even using our tiny example (shown again in Figure 9) the power of Linked Data becomes apparent. By linking your dataset it is possible to enrich it with new meaning.

Activity: Take a close look at the below figure where we have now labelled the relationships between the two sides of the diagram. Does this match what you were thinking of in the earlier activity with this diagram? Through enriching our data, we now know that the Dublin in our dataset is Dublin, Ireland and not Dublin, Ohio (where the Dublin Core metadata schema originated).

Figure 9: An example of a modelled dataset (right), linked to some external concepts (left)

Thing 8: Exposing - Define how people can get access to your LD: a data-dump, a SPARQL endpoint or a Web API.

After you expose your data, the next step is to think about your intended audience and how people will use and access the data. You will need to consider if and how you are going to expose your Linked Data “graph” as a whole. You have a few options for exposing your data and making it part of the LOD cloud. Access to the entire LD dataset must be possible via either RDF exploration, an RDF dump or a SPARQL endpoint. These options are further described below.

- Via RDF exploration: This refers to the ability to manually navigate the graph. It allows you to save the “breadcrumb trail” links from document to document and gather the results for searching.

- As an RDF (data) dump: RDF/Turtle is a human friendly serialization format, and one can describe the graph with provenance metadata (e.g. W3C-PROV) and accessibility information (W3C-VOID).

- As a SPARQL endpoint: Be careful because SPARQL is not very easy. It requires a background in query languages and one can easily get lost in the graph; the wrong queries can also put a very heavy load on the server. Initiatives like Puelia-PHP, RISIS-SMS and GRLC shield the SPARQL complexity by offering an abstraction layer (e.g. as a RESTful service) or visual components for pre-defined query templates.

_Activity: If you are curious to learn more about how queries are formed, visit the Wikidata Query Service. This service provides user friendly query examples which allow you to see how queries are formed and how the results are presented.

An alternative option is to use Linked Data fragments: Linked Data Fragments is a conceptual framework that provides a uniform view on all possible interfaces to RDF. A Linked Data Fragment (LDF) is characterized by a specific selector (subject URI, SPARQL query, …), metadata (variable names, counts, …), and controls (links or URIs to other fragments).

Thing 9: Promoting - Publish and disseminate the value of your data via visualisations and workflows

Once your data are out in the open, you can continue to link each of your statements (objects, subjects, predicates) to other statements in the LOD cloud (see Thing 7). But, you can also create other services on top of your data to tell the world how your data are equal, similar or different to other existing data

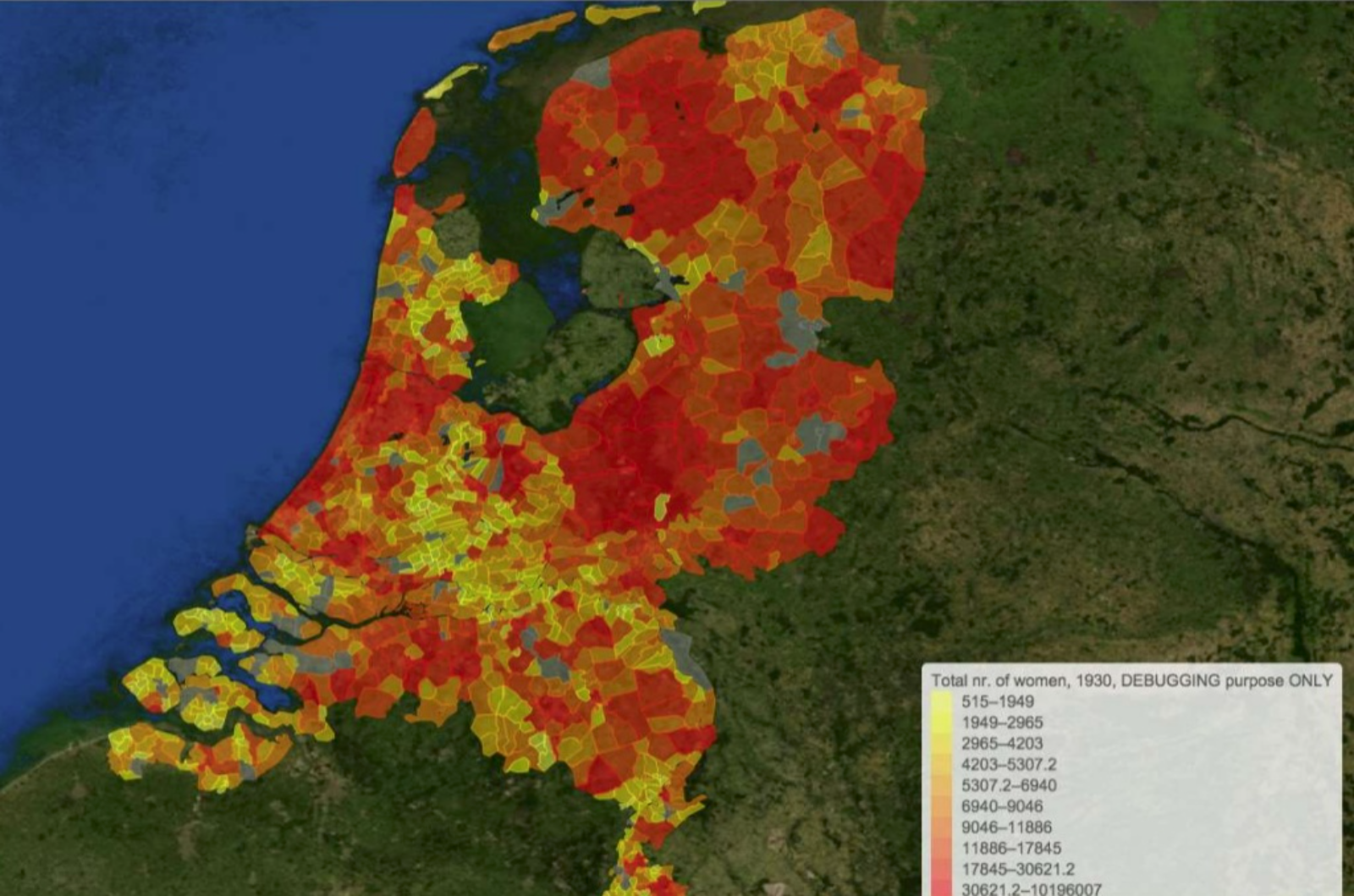

Activity: Visit https://www.cedar-project.nl/about/ to learn more about how linked open data are being used in the CEDAR project. Then, take a look at the below map, which Ashkan Ashkpour and Albert Meroño Peñuela created as a part of this project. To make the map, they combined linked data from the Dutch census with openly available geographic data to bring their research to life.

Figure 10: A map showing a combination of Linked Data from the Dutch census with geographic data - the heatmap shows the total number of female inhabitants

Thing 10: Sustaining - Ensure sustainability of your data

Publishing Linked Data into the LOD cloud is one specific instance of dealing with data on the web. The W3C recommendation “Data on the Web Best Practices” provides further pointers and considerations for many of the issues that we have raised here, such as the persistence of URI’s, version policy, or the reuse of vocabularies.

Many of the best practices listed in the W3C recommendation touch upon the importance of ensuring the sustainability of data publications in the immediate, mid- and long-term. These are also important for you to consider when publishing your data to the LOD cloud.

For example, it is important to associate a clear and preferably well-known standard license with your data and to present it clearly to the audience. You should also indicate if you maintain the right to change the license in the future. Standard content licences such as Creative Commons can be used for this purpose; licence information should be included in the served content. (See W3C Step #4)

Archiving a version of your RDF dataset as a static data dump in a certified, long-term stable data repository might also be a good option to help ensure the long-term sustainability of your data. This provides a way for you to preserve and potentially reuse all of the work that you have already invested. (see for an example Beek et al. 2016)

Activity: Examples of how to archive your RDF dataset can be found in the DANS EASY_1 data archive. Explore the below examples, paying particular attention to the associated readme-file instructions.

- The deposit of an RDF dataset from the CEDAR project

- The deposit of the Laundromat dataset

Publishing data as Linked Open Data is new for many researchers. Hopefully the steps, recommendations and references that we have presented here will help you to begin your own journey into the realm of Linked Open Data.

References

Beek, MSc W.G.J. (VU University Amsterdam); Rietveld, MSc L. (VU University Amsterdam); Schlobach, Dr. S. (VU University Amsterdam) (2016): LOD Laundromat (archival package 2016/06). DANS. https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-znh-bcg3

Dextre Clarke, S. Entry ‘Thesaurus (for information retrieval). Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organisation. Available at: https://www.isko.org/cyclo/thesaurus.htm

Hyvönen, E. (2012). Publishing and using cultural heritage linked data on the semantic web. Synthesis Lectures on the Semantic Web: Theory and Technology, 2(1), 1-159. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2200/S00452ED1V01Y201210WBE003

Hyvönen, E. (2019). Using the Semantic Web in Digital Humanities: Shift from Data Publishing to Data-analysis and Knowledge Discovery. submitted to Semantic Web Journal (under review). See: http://semantic-web-journal.net/system/files/swj2214.pdf;

Meroño-Peñuela, A., Ashkpour, A., van Erp, M., Mandemakers, K., Breure,L., Scharnhorst, A., Schlobach, S., van Harmelen, F. (2019). Semantic Technologies for Historical Research: A Survey. submitted to _Semantic Web Journal _(under review). See: http://www.semantic-web-journal.net/content/semantic-technologies-historical-research-survey

Moreau, L., & Groth, P. (2013). Provenance: an introduction to PROV. Synthesis Lectures on the Semantic Web: Theory and Technology, 3(4), 1-129. https://doi.org/10.2200/S00528ED1V01Y201308WBE007

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for pointers from and discussion with the DANS Research group, in particular from Herbert van de Sompel; and also for the valuable contributions of Esther Plomp, Marjan Grootveld and Enrico Daga. This document has been informed by the ‘GO FAIR Implementation Network Manifesto: Cross-Domain Interoperability of Heterogeneous Research Data (Go Inter)’ (Ed. by Peter Mutschke) https://www.go-fair.org/implementation-networks/overview/go-inter/ . The grants “Digging into the Knowledge Graph” and “Re-search: Contextual search for scientific research data” (NWO) have enabled part of this work.